Franz Clement: Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major (1805)

Franz Clement

born on 18 Nov. 1780 in Vienna

died on 3 Nov. 1842 in Vienna

First performance:

7 April 1805

(for comparison: first performance of the Beethoven Violin Concerto: 23 December 1806)

CD recommendations:

Rachel Barton Pie 2007

Mirijam Contzen 2019

Clement's first violin concerto was premiered on 7 April 1805 at the Theater an der Wien by the barely 25-year-old Clement himself, incidentally one year before Beethoven's violin concerto opus 61, which is also in D major. Coincidence or not, rather not. Beethoven held the Viennese star violinist Franz Clement in high esteem, who had been a child prodigy like Mozart and who celebrated great successes with his free fantasising on the violin. Clement was also involved as concertmaster in many premieres of Beethoven's works (including the opera Leonore and the Eroica). Beethoven was full of praise when, as early as 1794, he made an entry in Clement's pedigree book celebrating Clement as a great artist. Music critics also praised Clement's "indescribable daintiness, niceness and elegance, an extremely lovely tenderness and purity of playing" (1805 in the Leipziger Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung). It seems that Clement was influenced for the composition of his first violin concerto by Beethoven's piano concertos, which had already been written, in any case more than by Mozart's or Haydn's concertos. Incidentally, Clement also played the piano very well and had a phenomenal musical memory, for it is said that after performances of Haydn's Creation, in which he participated as a violinist, he made a piano arrangement based only on the libretto. As a practising violinist and as a composer, he followed what was happening compositionally and violinistically in his environment. Composing specifically for his solo instrument, the violin, was also common at the time, both in France (Rohde, Kreutzer) and in Germany (Spohr). And a little later, Paganini felt the need to show off his violin skills in his own violin concertos.

A year after his own first violin concerto, Clement wanted a concerto by Beethoven for the violin. And it is only slowly becoming known in musical circles that Beethoven took much from and

for Clement for his Violin Concerto. The view that Beethoven's Violin Concerto stands like an erratic block between the violin concertos of Mozart and Mendelssohn must be corrected. Incidentally,

Beethoven humorously wrote "Concerto par Clemenza pour Clement" over the score. However, it has been forgotten that Clement was the first interpreter to contribute many ossia passages of the

score of Beethoven's violin concerto to the definitive known violinistic figurations. As one can easily hear, Beethoven was influenced by Clement's first concerto and his violin artistry.

Conversely, in his second violin concerto in 1810, Clement would also adopt more of Beethoven's compositional style, as was common among composers at the time. The entire structure of Beethoven's

Violin Concerto in D major op 61, Apollonian lyricism (1st movement), floating melodies (2nd movement) and the final exuberant dance, can also be found in Clement's work. But Beethoven

radicalises this arrangement in his own way, as evidenced not only by the unusual beginning with the timpani beats, this sonorous symbol of the inexorable march of time! Nevertheless, it is worth

listening more closely to Franz Clement's Violin Concerto, in the knowledge that Beethoven's Violin Concerto did not yet exist, but that Beethoven had come to know and appreciate Clement's

concerto in Vienna.

Listen here!

1st movement

2nd movement

3rd movement

Listening guide:

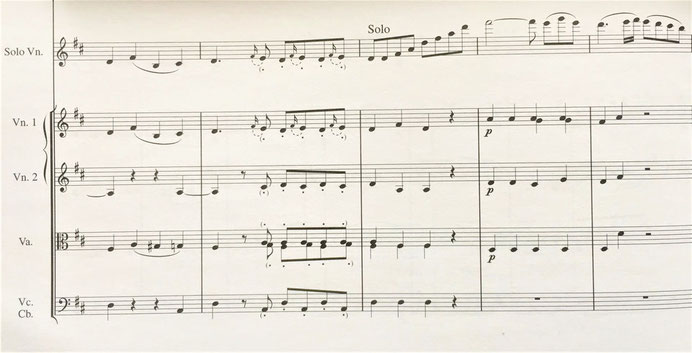

I. Allegro maestoso

A first theme advances rhythmically, colourfully passed through the instruments. It concludes triumphantly, before a swaying second theme appears, which, in addition to the strings, also features the flute. With an ascending run, the solo violin, which probably played along with the orchestral part according to the custom of the time, now resolutely claims the first theme for itself and continues it, plays with it and prepares the second theme and finds exchange and dialogue with the instruments of the orchestra (incidentally, the same orchestration as Beethoven's Violin Concerto later!). Already here, it is striking how the figurations of the violin repeatedly accompany prominent wind solos. This would not have been the case with Mozart. After another very colourful orchestral interlude, the violin enters in B minor, followed by a contemplative, almost sorrowful phase. The violin advances with figurations and runs. Then a march briefly appears in the orchestra. In dialogue with various instruments, the violin returns to the lyrical, friendly mood of the beginning. In the recapitulation, after the first theme, the lyrical second theme is heard peacefully. The winds (sometimes flute, sometimes clarinet, all together, and especially beautifully the bassoon) repeatedly come clearly to the fore. The final coda once again gathers all the power of the orchestra and all the virtuosity of the violin, which begins the obligatory cadenza. The orchestra concludes this movement in a resolutely invasive manner, which altogether depicted an ideal world in the style of Viennese Classicism.

II. Adagio

According to a contemporary review, Clement's violin playing had "an indescribable daintiness, niceness and elegance, an extremely lovely delicacy and purity of playing" (AMZ 1805, Sp 500). Unlike Beethoven, the second lyrical movement does not proceed in a searching and questioning manner, but rather sings with its own lightness, much like Clement's violin playing has been described. The violin begins its beautifully sung melody with an improvisation. One has the impression that the melody becomes even more beautiful, even more lyrical with each new entry. The orchestra takes over the melody and sings along. In a middle section (con più moto, i.e. somewhat faster in tempo), Clement shows off his playful violin runs and virtuoso figurations, while a wind choir performs a quiet chant of its own. In the recapitulation, the violin embellishes the melodies of the first part with ornaments of its own violinistic kind. Orchestra and violin remain in balanced unity, animating each other to almost ideal instrumental singing.

III. Rondo. Allegro

As in Beethoven's Violin Concerto a year later, the third movement begins in a dance-like manner. The violin starts in a swaying 6/8 time, dances forward until the orchestra joins in. Then the

violin presents double stops and technical subtleties, runs up and down, and returns again and again to dance-like happiness, often seconded by the winds. A moving in unproblematic joy.

The whole concert presents music that lets us listen to all the light and all the shades of lyricism, song and happiness, a humanism of happiness and balance beyond all the sorrow of the world.

The goal of art can also be: emotional recreation in playing together.