Vladimir Vogel: Concerto for violin and orchestra (1937); second version 1940

Vladimir Rudolfovich Vogel

born February 29, 1896 in Moscow

died 19 June 1984 in Zurich

First performance:

1938 by Suzanne Suter-Sapin in Brussels (first version).

1945 by Sandor Vègh in Geneva (second version).

Recordings:

Andrej Lütschg 1975 (on LP)

Bettina Boller 2000 (on CD)

Not only unknown, but almost forgotten, is a violin concerto that can be counted among the first radically modern violin concertos in music history, namely Vladimir Vogel's Violin Concerto

from 1937. After a period of experimentation, Vladimir Vogel's modern violin concerto, breaking away from late Romanticism, was written in the early 1930s. Numerous violin concertos, which today

are considered classical modern, were written during this period: for example, the violin concertos by Igor Stravinsky (1931), Alban Berg (1935), Arnold Schoenberg (1936), Sergei Prokofiev

(1937), Béla Bartók (1938), Benjamin Britten (1938/39), Paul Hindemith (1939) and Karl Amadeus Hartmann (1939). During this period, Vladimir Vogel, who fled Nazi Germany via Strasbourg, Paris,

and Brussels, finally came to Switzerland, was also looking for new ways to compose a violin concerto for a new era and a new audience. Influenced by his teacher Feruccio Busoni and connected to

German Expressionism, he, like Hans Eisler, sought ways to make Schoenberg's twelve-tone music fruitful for the future in the spirit of the anti-fascist socialist workers' movement. In this

context, he also specifically invented a type of choral speech singing that enriched the music.

In 1936 he received a commission to compose a violin concerto for the violinist Suzanne Suter-Sapin. An agreement was reached on a price of Fr. 3000. Wladimir Vogel completed the violin

concerto in late summer 1937, but it was not performed until November 16, 1938 in Brussels. In 1940 Vogel revised his violin concerto into a second version, which was premiered by Sandor Vegh in

Geneva in 1945. The concerto received an enthusiastic response from music critics, and numerous famous conductors (Erich Schmid, Räto Tschupp, Hermann Scherchen, Paul Klecki, and others)

performed it again frequently with violinist Andrej Lütschg in the 1960s and 1970s. (Cf. the performance list in Christoph Kloidt's seminal dissertation on "Wladimir Vogel's 'Concerto pour violon

et orchestre'", February 1998, p. 73).

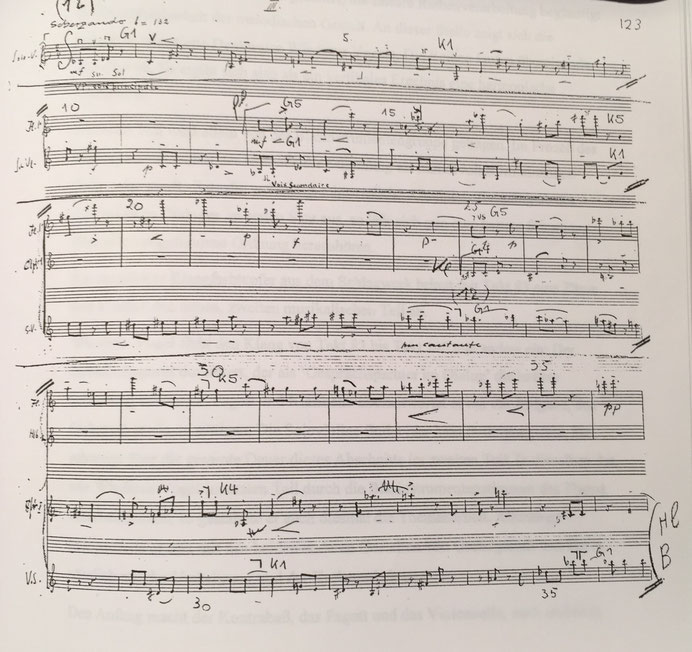

The second version, which can be considered definitive, was also recorded on LP by violinist Andrej Lütschg in 1975, and a CD with violinist Bettina Boller was released in 2000. A score is

still difficult to obtain today; the location of the musical sources is the Zurich Central Library, which has administered Vladimir Vogel's donation and estate since 1978.

The four-movement work is formally at the same time in three movements, because movement 3 and 4 form a certain unity. Moreover, the first two movements are composed in a freitonal manner,

while movements 3 and 4 use the twelve-tone technique in a form of their own. There are elements in the first movements that already anticipate elements of the serial principle. However,

according to musicologist Christoph Kloidt, it is precisely "the uniformity of the work as a whole that is an essential characteristic."

An introduction to the content of his violin concerto, which lasts about 40 minutes, was written by Vladimir Vogel himself for the 1975 recording: "Committed to the concerto form, the violin

concerto embodies a synthesis of virtuosity and concertante music-making, with the orchestra playing an important role, not just a conventional accompaniment. This requires almost equal

contribution from soloist, conductor and orchestra in the interpretation of the music. So the title of the work could just as well be 'Concerto for Violin and for Orchestra'. In addition to these

general observations, the conception of the piece should be noted. The four movements with their four characters also correspond to four manifestations: the representational-dynamic of the first

movement with its elevated, almost classical attitude; the lyrical-romantic of the second; the humorous of the scherzo and the double-meaning-turbulent of the finale. But the unifying and the

unified are achieved by the principle of the constructive, common to all the movements, as a compositional technique."

To be heard on streaming services only!

Listening Companion:

Movement 1: Introduction, Cadenza. Allegro non troppo e deciso

The "construction" of the first movement is formally subdivided into various blocks, which only hints at a sonata form in a broken way. Thus the movement begins quite unusually, but not

inappropriately for a violin concerto, with a cadenza by the solo violin. The orchestra accompanies with an ostinato motif that will be perceptible several times in the course of the entire

concerto. The violin plays upward reaching cadenza arabesques 7 times in succession. After a fanfare from the orchestra, more arabesques follow, tending downward. Then another fanfare blast, a

timpani roll, and it begins allegro ma non troppo e deciso a dance-like, gigue-like and light-footed, almost mechanical theme, first tending upward, then downward. The violin and the various

orchestral parts, led by trumpets, pass musical thoughts to each other as if in a relay race or even as if on an assembly line, according to Vogel "an expression of the precisely functioning and

coordinated play of the forces of our modern age." At the end of this block, a resolutely marking ff-fanfare is heard.

Short general pause. The mechanistic routine movement continues a big second lower - somewhat more mundane and quiet. Again the violin is in exchange with the other instruments of the orchestra

(low winds, then low strings). The closing fanfare is now played by the violin alone with the support of timpani and cymbals.

A third block follows, with always the same musical motifs in monotonous mechanics, however, the individual sound groups from the solo violin to the winds show themselves more individually, and

let fatigue be felt. At the end again fanfare of the whole orchestra.

A timpani roll is surprisingly followed by a solemn-sounding chorale-like brass section, which is taken over by the strings. The gigue-like dotted rhythm soon reasserts itself, however. Both the

solo violin and the orchestra, however, become more energetic, everything tending more and more in violent mechanics toward a common climax, which is then surprisingly reached with the return of

the violin's arabesque cadenza and the orchestra's ostinato motif, forming an open conclusion to a unified construction.

Movement 2: Lento

As in the first movement, the solo violin opens this approximately 17-minute lyrical-romantic movement with a cadenza alone, even without orchestral accompaniment, and strikingly with repeated glissandi. The violin takes its time settling into this new lyrical mood, developing the basic melodic and atonal elements of the movement out of initial uncertainty. At the end of the long cadenza, the strings present the theme already heard in the solo in its full form. Woodwinds take over the theme and develop it imaginatively. The clarinet then introduces a second cantabile theme, rhythmically accompanied by the solo violin.

After a brief violin solo interlude, a third theme follows again on the clarinet, counterpointed by flute and oboe, a quietly downward-flowing melody. In a next section, the strings take up the theme of the opening again. Over a restless orchestra, the solo violin takes up the downward-flowing third theme soloistically. More and more the three themes are linked together contrapuntally, without the lyrical romantic keynote of this song being dulled. The long path of this joint free-tonal singing of orchestra and solo violin leads back to the theme of the beginning, played by the solo violin. In a quiet sound field, this movement, which looks back almost somewhat nostalgically into the past, ends and leaves the field now attacca in the next movement to a new optimistic vision of the future.

Movement 3: Scherzando

Once again, this time "scherzando," the solo violin opens the movement. Rhythmically original, the violin makes a veritable twelve-tone row right at the beginning the melodic main theme of this

short scherzo, extended with 12 further tones of the row in the crab form to a linear melody comprising 24 tones. Twelve-tone music in comprehensible form becomes the program of the last two

movements of this violin concerto, written programmatically for the future of music. Immediately, the flute, clarinet, oboe and bassoon also take over the theme in its basic twelve-tone form in

the canon and then in the crab form. The whole is linearly audible, a kind of new polyphony replaces the old - cause for cheerful and joyful music of the future.

With the introduction of cymbals and timpani, a second part of this scherzo begins; double bass, bassoon and cello, violas and violins again open a new polyphonic section in succession,

determined in twelve-tone form by inversion and canker inversion of the theme. After that, the solo violin joins in again, and the cheerful interplay of the instruments increases in joint

dialogue.

The solo violin revitalizes the playing with the use of wild 32nd-note figures. A fortissimo brass part briefly recalls the chorale section of the first movement and breaks off abruptly at a

climax. Perkily and almost somewhat wittily, the solo violin, along with the oboe, revisits the beginning of the movement, but in inversion rather than in the basic shape. The violins follow in

pizzicato, the snare drum picks up the rhythm and falls silent.

Movement 4: Finale in modo die Mozart

Attacca follows with a surprise the shortest movement of the concerto (a mere 3 ½ minutes). The surprise: the solo violin opens the movement with a quotation from Mozart's Magic Flute Overture,

immediately recognizable but actually transformed into a twelve-tone row and followed by its cancer form, a kind of shockingly delightful "unexpected conundrum aural image." The typical feature

of this final movement is "the application of the twelve-tone row used in the preceding Scherzo movement to the model of the 'Magic Flute' overture" (Wladimir Vogel, Schriften und Aufzeichnungen

p. 129). And indeed, canon-like string instruments follow immediately after with various transpositions of the theme. Then the solo violin enters with the inversion of the theme. Vogel then

distributes the theme among various instruments.

A new section is then marked, as in the scherzo, again by the 32nd-note figures of the solo violin. Once again, all the voices of the orchestra concertize with each other in a kind of new

polyphony in euphonious twelve-tone technique.

A Presto closing section increases the tempo, and there is general unity towards the conclusion. There, the solemn brass passage resounds once again and leads to an eventful utopian final sound

of this programmatic future violin concerto.