Louis Spohr: Concertante No. 1 in A major for two violins and orchestra op.48 (1808)

Ludwig (Louis) Spohr

born 5 April 1784 in Brunswick

died 22 October 1859 in Kassel

Date of composition:

Spring 1808 in Gotha

CD recommendations:

Antje Weithaas, Mila Georgieva 1997/98

Ulf and Gundhild Hoelscher 2001

H. Kraggerud, O. Bjora 2008

Louis (Ludwig) Spohr acquired a highly substantial and outstanding reputation in the first half of the nineteenth century as a violin virtuoso, conductor, author, teacher and prolific

composer of over a hundred works. In terms of music history, he stands in the transition from the Classical to the Romantic period, but today he is usually only represented in concert programmes

with chamber music works (e.g. his Nonet in F major).

When studying his scores, one understands that Spohr declared himself a pupil of Mozart. For his works are classical in form. Nevertheless, they have little in common musically with Mozart's

sound world. Spohr was widely travelled and was also fortunate to meet numerous fellow composers by whom he was influenced. These included Clementi and Field in St. Petersburg, Meyerbeer and

Mendelssohn in Berlin, Beethoven in Vienna, Viotti and Cherubini in Paris and Weber in Stuttgart.

In the later nineteenth century, Spohr's post-classical style seemed too old-fashioned to those who had grown up with the heady sounds of Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Richard Strauss and others.

Still at this time Spohr's successful opera Jessonda op. 63 (1823), celebrated by Brahms and R. Strauss, remained popular and was often performed in Germany. In Britain, Spohr's oratorio The Last

Things (1826) proved a favourite of provincial choral societies until the First World War.

Among Spohr's works there are 18 violin concertos and 7 compositions for solo instruments and orchestra, five of which he called Concertante. Among the Concertantes published by Spohr

himself, there are two Concertantes for 2 violins, a rare instrumentation in the Romantic period, namely No. 1 in A major for two violins and orchestra op.48 and, as its counterpart, Concertante

No. 2 in B minor op.88.

Spohr composed the Concertante No. 1 in A major for two violins and orchestra op.48, at the age of 24, in the spring of 1808, during a creative phase in which he experimented with original

forms and complicated techniques. It comes across as a refreshing alternative to the usual repertoire, precisely because it was written for 2 soloists. Here's a guide to listen more

closely.

Listen here:

1st movement

2nd movement

3rd movement

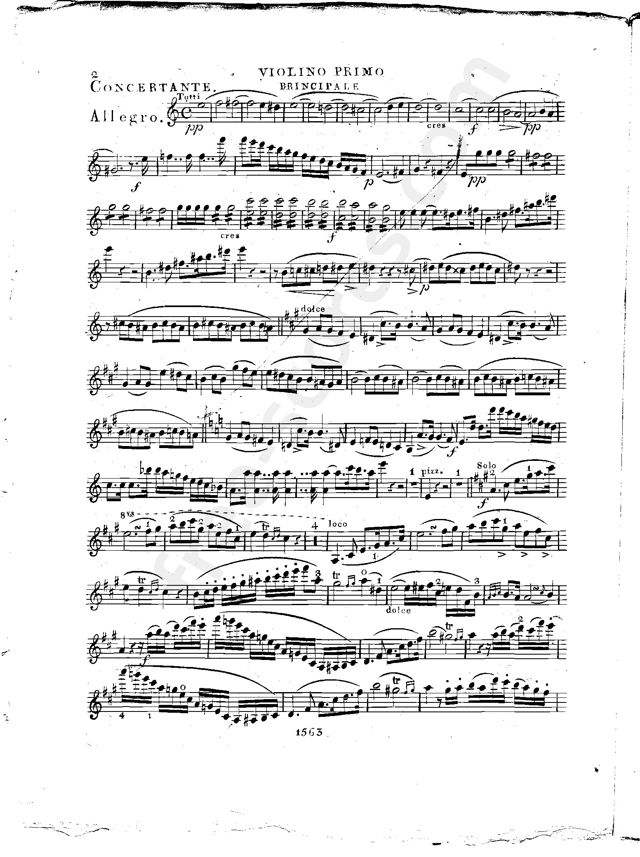

I. Allegro

The orchestral exposition slowly creeps out of the darkness, wind solos intoning a rising rhythmic motif in A major several times, leading to the first violent outburst. The motif turns out to be

the main theme, and announces itself again, this time in the cellos, answered by the winds. Thus the full orchestra leads over to the secondary theme, a swaying dolce theme with an accentuated

detour at the end, which now takes the lead in a fundamentally optimistic manner, only briefly clouded in a contemplative minor variant.

The orchestra's lead is thus made, and now the soloists take over the ascending A major main theme in unison octaves. Peacefully, together and relieving each other with glittering violin runs,

they illuminate this theme in luminous splendour. And again and again the violins seem to lose themselves in gimmicks of all kinds and high trills. In this way, they lead in a classically formal

manner to the lurching secondary theme, which they sing out and play around in two just as they do the first motif theme. With verve, the violins lead to the next orchestral interlude, which

imperceptibly leads into the development and allows an almost somewhat wistful third theme to emerge, the violins following contemplatively and in a minor key.

Then the rising motif follows again, fluctuating between major and minor and with virtuosic, wild runs. Imperceptibly, it leads out of the development until the violins take over the motif theme

again in decisive A major. The secondary theme, too, appears again in detail, but now in a new dark colouring. Then the violins, together with the orchestra, rush forward in a spirited rush to

the conclusion of this life-affirming movement. Throughout the movement, Spohr succeeds in giving sufficient personality to the wind parts in addition to the virtuoso violins.

II. Larghetto

A dreamlike melody filled with poignant semitones, always played on the dark G-string of the violins, opens a mystical space, and thus opens the central Larghetto, for me one of Spohr's most romantic slow movements, which was also described by the music writer Hartmut Becker as "a musical gem of a special kind". After a brief hesitation in the music, a middle section follows, characterised by a running orchestral pizzicato, over which the violins let all their sweetness of thirds and sixths ring out. Then, in the third part, the dreamlike melody in the string orchestra sound recalls the beginning again, the violins play excited semiquavers, but the simple C major conclusion reconciles.

III. Rondo - Allegretto

Following the example of the classics Haydn and Mozart, here is the Rondo Dance of a violin concerto. The theme is teasing and jocularly buoyant. This cheerful finale goes without saying, is rich in gallant tones (and animating horns). Every now and then, a special orchestral effect follows, which caused particular astonishment in Spohr's day. A harsh interlude rides in between, but the violins celebrate their skills. Again and again, as one would expect from a rondo, the teasing, dallying rondo theme comes in and leaves us in high spirits.