Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Concerto pour violon A major, Op. 5 No. 2 (1775)

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges

born 25 Dec. 1745 in Baillif, Guadeloupe

died 10 June 1799 in Paris

First published:

1775 in Paris by Mr Bailleux

Recordings:

Jean-Jacques Kantorow 1974

Rachel Barton 1997

Takako Nishizaki 2000

In order to appreciate the music of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint Georges, as music in its own right, I avoid the label of "Black Mozart" attached to the Chevalier and prefer to speak of

an important representative of French classical music (as a counterpart to Viennese classical music). Joseph Bologne, who was ennobled as Chevalier de Saint Georges because of his merits in

fencing and music, oriented himself on the music and composers of his time in the Paris of the emerging bourgeoisie. In music, too, there was a trend in Paris towards upheaval and new beginnings,

away from the aristocratic court to the bourgeoisie's own orchestral events. A foreshadowing of what was also violently implemented socially at the end of the century in the French

Revolution.

Likewise, I do not want to interpret Saint-George's compositions from his particular fate in life, even though his life was highly impressive, moving and inspired many novelistic fantasies

(beginning with his birth as the child of a slave in Guadelupe, through his rise into aristocratic circles as "the most accomplished man in Europe in riding, shooting, fencing, dancing and music"

(John Adam), to his role in the French Revolution and his opposition to Napoleon because of his reinstatement of slavery!)

Nothing is known about Saint-George's musical training. But it is worth looking at the composers who later influenced him musically. Musical influence on his style as a composer certainly

came from composers who had dedicated works of their own to him. For example, the Italian violinist Antonio Lolli (1725-1802) composed two violin concertos for him, François-Joseph Gossec

dedicated the Six String Trios Op. 9 to him, other dedications came later from Carl Stamitz (1745-1801) and other less well-known musicians. Jean Marie Leclair (1697-1764) and Pierre Gaviniès

(1728-1800) probably influenced him as a violinist.

Saint-George's musical style was thus influenced by the Italian violin concerto tradition, the symphonic world of Gossec, the Mannheim School and his own emerging French violin school. This

results in a thoroughly exciting mixture, which Saint-Georges brought together to form his own brilliant style of composition in the 18th century of the Enlightenment and from which a rich oeuvre

of string quartets, violin concertos, symphonies concertantes and operas emerged. His musical talent was recognised by his contemporaries. As a musician, he succeeded François-Joseph Gossec as

conductor of the orchestra Concert des Amateurs, which quickly became famous throughout Europe for its performances of contemporary symphonic compositions. Saint-Georges conducted the world

premieres of Haydn's so-called Paris Symphonies. The fact that he also repeatedly excelled with his technically demanding violin concertos and his concertante symphonies was certainly also

noticed by Mozart during his visit to Paris. According to some musicologists, Mozart even adopted this peculiarity, typical of Saint-George's violin concertos, of having the sequence of rapid

upward scales on the E string followed by abrupt low notes on the G string, in his own Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola (K. 364).

But the fact that Saint-George's works have hardly been played today and have been forgotten is hardly due to their real originality. This might have more to do with the emerging cult of

genius during the Romantic period. Even Voltaire thought mulattos had little intellectual originality. The assessment of an opera by Saint Georges by the actually cultivated contemporary Baron

Melchior von Grimm is most revealing:

" Cette pièce est mieux écrite qu'aucune autre de Monsieur de Saint-George. Et néanmoins elle

apparaît également dépourvue d'invention. Ceci rappelle une observation que rien n'a encore

it is that nature has served the mulâtres in a special way by providing them with a

aptitude merveilleuse à exercer tous les arts d'imitation, elle semble cependant leur avoir refusé cet

élan du sentiment et du génie qui produit seul des idées neuves et des conceptions originales" (cf. Michelle Garnier-Panafieu, Un contemporain atypique de Mozart : Le Chevalier de

Saint-George, YP Éditions 2011).

In the period of genius cult that emerged after Joseph Boulogne's death, he was somehow remembered as a virtuoso and brilliant performing musician, but he became insignificant and forgotten

as a genius. Such racial prejudices, as well as comparisons with Mozart, prevented us until recently from perceiving the independence of Saint-George's rich oeuvre and its compositional

significance and development.

My aim here is to listen anew to a violin concerto by Saint Georges with a personal listening aid, in order to be carried away by this self-confident music from the Age of Enlightenment and

its infectious joie de vivre and courage to be oneself. That a rich and complex emotional world also comes close to us in the process can be experienced when listening to the second

movement.

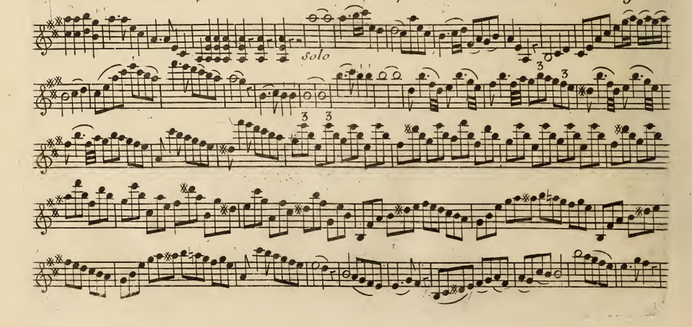

Here the concerto can be heard in a brilliant

recording!

Listening companion:

1. Allegro Moderato

The orchestral exposition of the then customary orchestra (strings, 2 oboes and 2 horns ad libitum) brings one theme after the other in free succession, one more gallant and beautiful than the

other. At first, a theme that starts immediately in syncopation attracts the listener's full attention. Its postlude seems to come towards us listeners until it leads back to the repetition of

the syncopated theme with a tutti start. Then again a full Mannheim crescendo in the tutti, followed by a melodiously singing, questioningly gentle theme that ends abruptly with three

thematically striking, violent final chords. A new moving interlude begins and leads into more melancholy areas of feeling, but these are quickly wiped away again.

Then - after a brief pause - another dallying theme surprises us, until those three striking chords already heard bring this rich orchestral exposition to an end.

Enter the soloist: with a long-drawn-out A, the violin finally steps forward from an imaginary background into the orchestral play, bringing a new thematic idea for the orchestra. In

self-confident ups and downs, the violin affirms this own theme and at the same time continues it as if the themes presented by the orchestra were not enough for it. The violin shows courage to

do its own thing and makes use of its own technical skills. Only then does the violin take over the second questioning, gentle theme, after which it rises to the highest virtuoso heights of its

own. After a short tutti, the violin then remembers the dallying-dancing theme of the orchestral introduction and transforms it into virtuoso violin figurations and runs, which, for example,

after an ever-rising scale to the highest e, abruptly plummet to the low b on the G string, only to be caught by the orchestra's tutti. The orchestra takes over the dallying theme and continues

it in wild runs until the violin enters anew on a long-drawn-out e. Underneath, a previously introduced theme can be heard. Below this, an orchestral motif that has already been introduced can be

heard, but then there is no stopping the violin, it shows what it can do and boldly goes ahead of everyone until it stops briefly after a free cadenza on a high b. But immediately the violin

falls. But immediately the violin plunges ahead again with a brisk rhythmic motif. Now and then, between violinistic skills, memories of the given themes emerge. In long attempts of all kinds,

the violin prepares us for an obviously very important tutti. And really: full orchestral effort: a motif played by the basses, reminiscent of the main theme, and a movement striding towards us

lead immediately to the orchestra's gentle second theme as a hidden recapitulation. Again, this finely balanced theme closes with strikingly violent, triple final chords.

Once again the solo violin takes the lead and again brings its own first confident solo theme. But then, as if to reassign itself to the orchestra, it flows formally faithfully into the gentle

second theme and leads it into technical escapades of the heightened kind. Pizzicati of the orchestra accompany benevolently at times. Occasionally, the violin recalls the dallying dance.

But once again, the solo violin shines and takes ample time and space to display its skills. With the three familiar fierce final chords, however, the orchestra takes over and leads the music to

its own extensive orchestral moderato conclusion.

II. Largo

The brilliant first movement is followed by an emotional Largo. Saint-Georges thus follows the new three-movement concerto form introduced by the Italians, which does not simply string together

courtly dances (as in the French suite) but seeks to address the emotional world of the enlightened bourgeois subject. In the subdominant of A major, a touching, chant-like D major melody of the

string orchestra begins with an upbeat in regularly stepping triple time. Slightly melancholic and occasionally cloudy in the minor key, it directly touches the listener's emotions and thus

prepares the way for the solo violin. Here, too, the violin does not simply take over the beautiful vocal theme, but begins with two long drawn-out notes in A and an optimistic ascent to the high

D and then slowly descends over the accompanying triple rhythm of the orchestra to the end of the melodic phrase. But immediately she resumes her dreamlike singing, the kind that seems destined

only for a violin solo, leading into spheres that made the violin the ideal modern solo instrument in France at the time. One follows enlightened and sees light in the darkness of existence. A

contemplative tutti only briefly interrupts the singing of the violin. The animating triple rhythm of the orchestra immediately invites the violin again to repeat its optimistically ascending

opening motif, though now somewhat lower in E, and to lead the melody once more through the most beautiful regions of the violin's sound. And finally the violin takes over the orchestra's opening

theme and reveals in the most beautiful violin register what this melody contains in terms of motivic richness, movement and beauty. Slowly, she leads this melody to a peaceful end, not without

convincingly demonstrating empirically the height of a violin's tonal range that is attainable. Then follows the expected cadenza and a fine fade-out by the orchestra.

III. Rondeau

In classical openness to tradition, the proud bourgeois solo violin now generously takes over a dance from the French suite structure in the third movement: it leads a rondeau in somewhat stiff

2/4 time (without plunging stormily into a rondo of Italian violin concertos, but remaining rather courtly cosy for all its joie de vivre). The orchestral tutti takes over and gives the rondeau

theme fullness. Then the solo violin again takes the lead in virtuoso fashion, varying motifs from the theme and, after a fermata, inviting the audience once more to the rondeau dance, which the

orchestra joyfully follows with its full instrumentation. Then, however, the solo violin breaks into the dance action with an excited minore episode in A minor, defiantly asserting itself, but

without greatly disturbing the general rhythm. As if pleased, the orchestra supports the violin's rhythm in festive C major, but only briefly: the violin takes over with violinistically brilliant

figurations, without disturbing the celebration, until it decisively reasserts its self-determined minore theme, only to let the minore section run out in excited virtuoso ups and downs as it

continues, and to lead back dutifully into the general rondeau dance. After this repetition of the rondeau, however, the violin takes all the liberties it can in its final episode, plunging

spicatissime into 16th-note figures, conjuring virtuoso runs up to the highest registers, alternating between rapid changes of register and octave playing, and letting its full resonance ring out

in daring barriolage figurations and wild sextuplets. Here the soloist can show the astonished audience what is possible in the future with practice, technique and training. However, the soloist

leaves the conclusion of this violin concerto to the familiar round dance of the orchestra, which brings everything back to normality in a socially compliant manner.