Carl Reinecke: Violin Concerto in G minor op 141 (1876)

Carl Reinecke

born 23 June 1824 in Altona

died 10 March 1910 in Leipzig

First performance:

21 Dec. 1876 in Leipzig by the violinist Joseph Joachim

CD recording:

Ingolf Turban 2004

It does not exactly arouse interest in a composer when, like Carl Reinecke, he says of himself: he does not want to "oppose it when people call me an epigone". He was also convinced towards

the end of his long life that his works would hardly survive. And this comes from someone who composed more than 300 compositions in all musical genres with intoxicating energy. Performance and

self-confidence do not coincide there. For he made a career as a pianist and as a conductor. He held highly respected positions: as leader of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and as composition teacher

and later director of the conservatory in Leipzig. The list of his pupils is large, but he was offended by his dismissal as chief conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra after 35 years. He was

replaced by a younger conductor, Arthur Nikisch.

He was also unhappy with his Violin Concerto in G minor. The first performance was given by Joseph Joachim on 21 December 1876, but Joachim did not include it in his repertoire, probably

because he was soon involved in the preparation of Brahms' Violin Concerto (1976-78). And Brahms' Violin Concerto brought a new dimension to the genre of violin concertos, and Reinecke's concerto

was no longer played because all the other violinists shunned the work because as was owned by Joseph Joachim. Joachim, however, now played and promoted his Brahms Concerto everywhere after its

premiere in 1878. Only today does Reinecke's Violin Concerto have a chance of being heard again, at least initially on recordings. The concerto belongs to the tradition of the classically

romantic violin concertos by Mendelssohn (première: 1845), Schumann (composed in 1853, première: 1937), Bruch (première: 1866), Dietrich (première: 1876). So Reinecke's Violin Concerto (1878) is

not that epigone-like. However, neither oblivion nor epigony should prevent one from appreciating the quality of this concerto and feeling one's way into its romantic melodic and tonal world.

This was conveyed to me by the booklet text of Matthias Wiegandt's CPO recording, excerpts of which I am happy to include in the listening guide, because I find this concerto very worth listening

to and could not describe it better.

Listen here!

Listening guide:

I. Allegro moderato

"In the concerto as a whole, Reinecke emphasizes melodically succinct themes but without aiming at the exaggerated showcastin of pretty ideas. The compact opening tutti of the first movement

expounds the primary theme (G minor) and takes it to the first point of culmination. The soloist enters with the theme head in the dynamic downswing of the orchestra and brings the principal idea

to full unfolding. After a short transition, he establishes a new theme (B flat major). The many adornments of the melodic main degrees number among the qualities typical of Reinecke - which is

why so many a phrase reaches its goal note only after delicate evasive manoeuvres.

The middle tutti avails itself of both themes and has the primary theme sound forth in a triumphant major at the dynamic high point. Again the soloist is given the opportunity to use quickly

following reduction as a stage for his entry and to render audible the lyrical appeal of the theme modulated to major. The recapitulation is reached after an imposing intensification comparable

to an analogous passage in Bruch's G minor concerto. Reinecke reserves the most powerful moment for the preparation of the cadenza, in which the orchestra booms in triple forte, but executes the

transition with a pizzicato version of the head of the primary theme (Ingold Turban plays this measure additionally as a solo echo)." (Booklet text by Matthias Wiegandt)

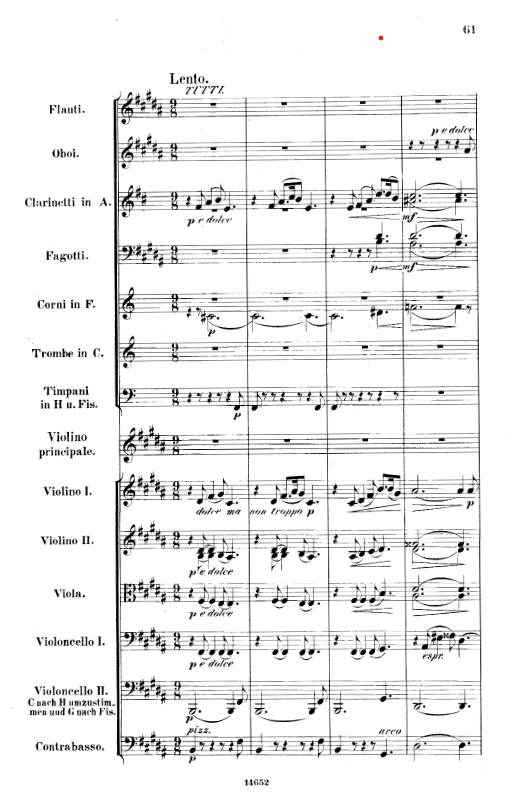

II. Lento

In the calm blend of clarinet and orchestral violins, a vocal scene begins in a swaying 9/8 time, whose catchy romantic B major song theme is immediately sung along by the oboe, before the solo

violin then makes this song without words its theme. The romantic mood is deepened by the horn singing, while the solo violin continues to sing the theme in all registers, varying and exchanging

with the orchestra.

Then a change of harmony: slight mysterious darkening. The oboe intones the song again a fifth lower, the solo violin improvises around it and leads to a clarinet solo "con gran espressione". New

timbres for the same lento melody!

Then a tutti from the orchestra brings a passionate upswing and new impulses to this song scene, but the song theme cannot be displaced. It reappears again and again. Singing itself out, it

evokes romantic feelings and moods that continue to resonate beyond this movement to the final movement and beyond... or in Felix Mendelssohn's words: it is "music that fills one's soul with a

thousand better things than words". (Letter to Marc-André Souchay, 15 October 1842) (Text: TB)

III. Finale. Moderato con grazia

"The finale becomes the scene of a highly effective dramaturgy. At the beginning Reinecke appropriates the idea, familiar since Beethoven, of haveing the key of the slow movement continue to echo

before the new G major tonic is modulated and the refrain material is set forth. The orchestra spreads its little veil of stage mist and plays with the potential for conflict, unexspected at this

juncture. When the feint is detected, the shadows yield to an exemplary rondo theme in the solo instrument. For more than two minutes the soloist and orchestra play with this idea, until it is

time for a first episode. But what now emerges transcends this function. The highly effectiv shifts of register and character on the part of the solo violin may be interpreted as the inner

monologue of a stage figure who goes back and forth between self-doubt and emphasis. The idea of a dialogue seems even more obvious. At first a pessimistic voice is heard in minor, with its

melody line pointing downward and realizing one of Reinecke's rare 'grandioso' tasks. The lingering in the abyss is answered by an optimistic descant voice with the major version of the

cantilena. The ensuing evolution of the theme remains in a state of suspension between doubt and assuagement.

The recurrncee of the refrain is followed by a dramaturgical surge. Instead of the expected second epsode, the principal idea of the lento movement is drawn on. Now incorporated into the

metrical structure of the finale, it presents new, animated facets of its beautiful identity. For its part, the solo violin finally seems to understand, after the recapitulation of the

refrain and the modified dialogue material, how limited the portion of extroverted playing episodes is within the movement. It promptly undertakes a concluding intensification.

Its weakness of will nevertheless can be read from the fact that it immediately allows itself to be enticed by the orchestra to pick up on the lento theme now intoned. The last

retarding element nevertheless at some point is used up, which is why those involved summon up their energie and bring about the appropriately pompous conclusion." (Booklet text by Matthias

Wiegandt)