Louis Spohr: Concertante No. 1 in A major for two violins op.48 (1808) Violin Concerto No.9 in D minor op. 55 (1820)

Ludwig (Louis) Spohr

born 5 April 1784 in Brunswick

died 22 October 1859 in Kassel

Date of composition:

Concertante No.1 A Major for two violins: Spring 1808 in Gotha;

Violin Concerto No.9 d-minor: 1820

CD recommendations:

Concertante No.1 A Major for two violins:

Antje Weithaas, Mila Georgieva 1997/98

Ulf and Gundhild Hoelscher 2001

H. Kraggerud, O. Bjora 2008

Violin Concerto No.9 d-minor:

Erica Morini 1963

Christiane Edinger 1993

Ulf Hoelscher 1993

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Louis (Ludwig) Spohr acquired a highly substantial and outstanding reputation as a violin virtuoso, conductor, author, teacher and prolific

composer of almost 300 works. In terms of music history, he stands at the transition from the Classical to the Romantic period, but today he is usually only represented in concert programmes with

chamber music works (e.g. his Nonet in F major).

When studying his scores, one realises that Spohr declared himself to be a pupil of Mozart. His works are classical in form. Nevertheless, they are musically distant from Mozart's world of sound.

Spohr travelled widely and was also fortunate enough to meet numerous fellow composers who influenced him. These included Clementi and Field in St Petersburg, Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn in Berlin,

Beethoven in Vienna, Viotti and Cherubini in Paris and Weber in Stuttgart.

In the later nineteenth century, Spohr's post-classical style seemed too old-fashioned to those who had grown up with the intoxicating sounds of Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Richard Strauss and others.

At this time, Spohr's successful opera Jessonda op. 63 (1823), which was celebrated by Brahms and R. Strauss, remained popular and was often performed in Germany. In Great Britain, Spohr's

oratorio ‘The Last Things’ (1826) proved to be a favourite of provincial choral societies until the First World War.

During his many years as a musician, Spohr worked at an interesting turning point in the understanding of music. Music began to emancipate itself from the predetermined structures of princely

courts or churches and wanted to make a new contribution to the education of the individual, who no longer wanted to see his enlightened self-worth founded in his birth, but in his own ‘work’,

‘endeavour’, ‘elevation’ and ‘ennoblement’ (cf. Spohr's self-biography 1860/I, 31, 34, 1861/II, 404).

Louis Spohr: Concertante No. 1 in A major for two violins op.48

Among Spohr's works there are 18 violin concertos and 7 compositions for solo instruments and orchestra, five of which he called Concertantes. Among the concertantes published by Spohr

himself are two concertantes for two violins, a rare instrumentation in the Romantic period, namely No. 1 in A major for two violins and orchestra op. 48 and its counterpart, the Concertante No.

2 in B minor op. 88.

Spohr composed the Concertante No. 1 in A major for two violins and orchestra op. 48 at the age of 24, in the spring of 1808, during a creative phase in which he experimented with original

forms and complicated techniques. It comes across as a refreshing alternative to the usual repertoire, especially because it was written for two soloists.

Listen here:

1st movement

2nd movement

3rd movement

Listening guide:

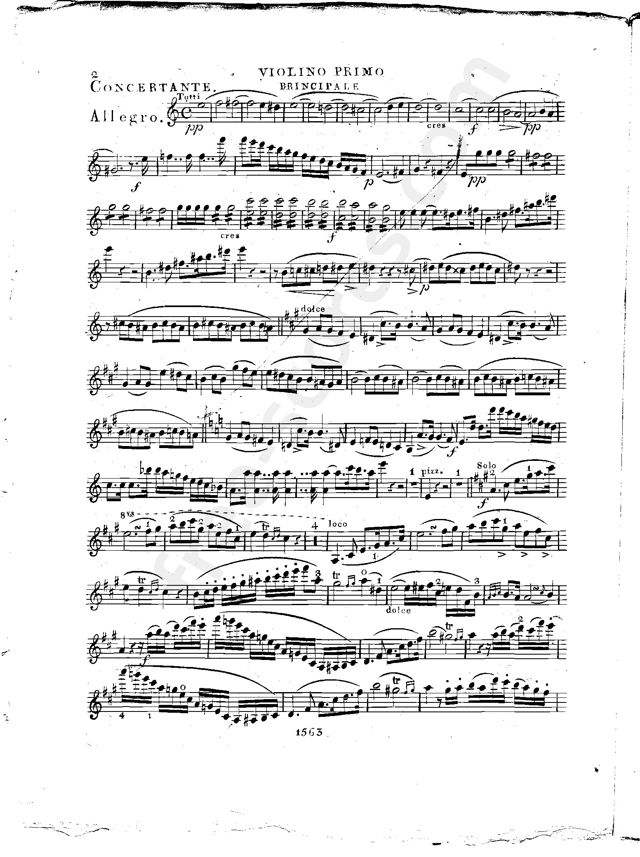

I. Allegro

The orchestral exposition slowly creeps out of the darkness, wind solos intoning a rising rhythmic motif in A major several times, leading to the first violent outburst. The motif turns out to be

the main theme, and announces itself again, this time in the cellos, answered by the winds. Thus the full orchestra leads over to the secondary theme, a swaying dolce theme with an accentuated

detour at the end, which now takes the lead in a fundamentally optimistic manner, only briefly clouded in a contemplative minor variant.

The orchestra's lead is thus made, and now the soloists take over the ascending A major main theme in unison octaves. Peacefully, together and relieving each other with glittering violin runs,

they illuminate this theme in luminous splendour. And again and again the violins seem to lose themselves in gimmicks of all kinds and high trills. In this way, they lead in a classically formal

manner to the lurching secondary theme, which they sing out and play around in two just as they do the first motif theme. With verve, the violins lead to the next orchestral interlude, which

imperceptibly leads into the development and allows an almost somewhat wistful third theme to emerge, the violins following contemplatively and in a minor key.

Then the rising motif follows again, fluctuating between major and minor and with virtuosic, wild runs. Imperceptibly, it leads out of the development until the violins take over the motif theme

again in decisive A major. The secondary theme, too, appears again in detail, but now in a new dark colouring. Then the violins, together with the orchestra, rush forward in a spirited rush to

the conclusion of this life-affirming movement. Throughout the movement, Spohr succeeds in giving sufficient personality to the wind parts in addition to the virtuoso violins.

II. Larghetto

A dreamlike melody filled with poignant semitones, always played on the dark G-string of the violins, opens a mystical space, and thus opens the central Larghetto, for me one of Spohr's most romantic slow movements, which was also described by the music writer Hartmut Becker as "a musical gem of a special kind". After a brief hesitation in the music, a middle section follows, characterised by a running orchestral pizzicato, over which the violins let all their sweetness of thirds and sixths ring out. Then, in the third part, the dreamlike melody in the string orchestra sound recalls the beginning again, the violins play excited semiquavers, but the simple C major conclusion reconciles.

III. Rondo - Allegretto

Following the example of the classics Haydn and Mozart, here is the Rondo Dance of a violin concerto. The theme is teasing and jocularly buoyant. This cheerful finale goes without saying, is rich in gallant tones (and animating horns). Every now and then, a special orchestral effect follows, which caused particular astonishment in Spohr's day. A harsh interlude rides in between, but the violins celebrate their skills. Again and again, as one would expect from a rondo, the teasing, dallying rondo theme comes in and leaves us in high spirits.

Louis Spohr: Violin Concerto No. 9 in D minor op.55

Louis Spohr's best-known violin concerto is undoubtedly Concerto No. 8 (in A minor ‘In the form of a song scene’). Spohr's most compositionally accomplished violin concerto is Concerto No. 7

in E minor, at least according to connoisseurs of all Spohr's works. However, Spohr's least known and best violin concerto is Concerto No. 9 in D minor. After all, Spohr included the violin part

of this concerto in his own ‘Violin School’ and wrote a second part to accompany it. Spohr wrote this concerto in D minor in 1820 for his own Europe-wide travelling activities as a solo

violinist. From 1822 and his appointment to Kassel, he concentrated more on his conducting activities and musical life in Kassel.

Listen here:

Movement 1

Movement 2

Movement 3

Listening companion:

Allegro

A longer orchestral exposition repeatedly introduces a rhythmically concise D minor theme that moves forwards and upwards and immediately answers it with a soft dotted fade-out. This motif

characterises the orchestral introduction until the violin begins its solo episode with a rapid chromatic run-up and opens its lyrical striving with a theme that resembles the echo of the

orchestral main theme. In this way, the violin solo establishes a continuing contrast to the pathetically serious orchestral opening. After elegant figurations, the solo violin introduces the

actual second lyrical theme, whose concise motif is immediately repeated - effectively an octave lower.

The orchestra then marks the beginning of the development section with full force, confronting and interweaving the concise main motif and the lyrical secondary themes of the violin.

The main motif appears again in the recapitulation, but now in D major. Spohr's musical idea of elevating and ennobling the spirit can also be heard in the increased recurrence of the lyrical

secondary themes. Spohr deliberately renounces a purely external, self-expressive cadenza for the solo violin. The music leads directly to an effective and self-determined concerto conclusion.

Adagio

The Adagio also begins resolutely active, as in the first movement, before leading into a wistful, romantic melody accompanied by a pizzicato bass and expanding into a noble song that uplifts the

spirit and mind.

A brief excited interlude is only a brief disturbance and distraction before the music can lyrically concentrate again on its task of ennobling the violinist and listener together. The melody

rises beautifully until it quietly fades away.

If listeners want to follow the idea of this music, this Adagio may remind them of a sentence from Spohr's autobiography, where he says that he cannot imagine bliss in the mere contemplation and

worship of God; rather, the spirit must also be able to strive and work beyond, and there must also be music there, although it will be different from ours (cf. Selbstbiographie II, 1861, 404).

Allegretto - Rondo

A horn calls out of the silence and awakens the violin to an enchanting rhythmic dance that melts into double stops. The orchestra accompanies pizzicato and discreetly, which encourages the

violin to continue its serenade with delight.

The orchestra then leads just as discreetly into the first couplet of this rondo movement. In this couplet, the violin takes centre stage again with a series of bold and virtuoso leaps, leading

to a variation of its dance theme and virtuoso additional figures. Only an energetic interjection from the orchestra leads the violin back to its enchanting theme.

After a further orchestral transition, a second couplet follows. Once again, the violin leaps wide, again free variations on the dance theme and further virtuoso figurations, before the charming

little dance returns and wants to be nothing other than music.

An orchestral coda then gives the solo violin an original final appearance, of course once again with virtuoso double-stop magic.