Grażyna Bacewicz: Violin Concerto No. 7 (1965/66)

Grażyna Bacewicz

born 5 Feb. 1909 in Łódź,

died 17 Jan. 1969 in Warsaw

First performance:

13 Jan. 1966 in Brussels by Augustin Leonara (to whom the composition is dedicated).

CD recording:

Joanna Kurkowicz (2009)

Among the seven violin concertos by the Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz, the last, seventh violin concerto stands out because it testifies to the personal development of an original composer

away from a neo-classical style of composition towards her very own new sound possibilities of a violin concerto. As a violinist and composer, Grażyna Bacewicz knew the possibilities of sound and

playing variations that lie within a violin. She often played the concertos of Karol Szymanowski; the 7th Violin Concerto in particular joins these concertos in a new way. When the Polish music

world moved away from the constraints of socialist realism in the 1960s and opened up to serial and tonal experiments in contemporary music of the time, Polish composers such as Lutosławski,

Penderecki, Tadeusz Baird and others created their compositions, which caused a sensation at the time. Although Bacewicz was a well-known violin soloist and composer during her lifetime, not only

in Poland but also internationally, her works fell into unjustified oblivion after her relatively early death (1969), both in Poland and especially internationally. At the time of the composition

of the 7th Violin Concerto, Bacewicz herself was no longer able to perform as a soloist due to the consequences of a car accident, so the composition of a last violin concerto probably took on a

special meaning for her. Once again, she explored the possibilities of modern violin technique, but also opened up new possibilities for the interplay of violin and orchestra, which not only

played an accompanying role, but also acted as a sound subjet. Already in the 6th Violin Concerto she confronted these new possibilities, but was not satisfied with the result, so she did not

publish this 6th Violin Concerto and took over elements from it for other new compositions. Her 7th Violin Concerto was awarded a gold medal at the Queen Elisabeth International Composition

Competition in Brussels in 1965. It was also premiered in Brussels, but since then it has not been included in the repertoire of contemporary violin concertos. High time, then, to immerse

yourself in the fascinating sound world of this violin concerto, whose otherwise simple orchestration is strikingly reinforced with vibraphone, celesta, bongos and two harps.

Listen to it here on Youtube!

Listening companion:

I. Allegro

A whip-crack at the beginning, shrill wind chords, fading downwards. An advancing rhythm in the first violins passes by and fades away. Celesta and vibraphone sounds reverberate, this striking rhythm appears again, rising briefly to a kind of Viennese waltz prelude, whereupon the violin enters prominently, with an unusual solo melody that winds around seconds, singing itself out again and again "up and down", quietly accompanied by the strange celesta, harp and wind chords, until the solo violin finally glides in a long run-up to the highest heights. The driving rhythm interferes violently with the trumpets for a moment, bringing the violin down and causing it to intonate a new motif. It is a double-stop play circling around the note a (a dissonant interval filled within a minor third), freely reminiscent of a second theme of a sonata form, but which will be a defining feature throughout the entire concerto. But the motif quickly fades away into lonely emptiness, accompanied by strange sounds. Again, the orchestra's shrill wind outburst, almost as at the beginning, which challenges the violin to new ups and downs. Twice more, the violin subtly brings its second motif to the oppressive sounds of the winds, then the violin flees into wild runs, brings new rhythms, colours, sounds, plays sul ponticello rich in overtones, as if it wants to make sure of all its abilities. But again it is beset by the garish sound of the wind orchestra, which seems to gain the upper hand, but then disappears in a strange void. Then the violin begins its cadenza, which starts with a melody slowly gliding down in seconds, which will appear again in the second movement, then circles around its beloved second again, developing its own sound possibilities, now alone for itself, with the orchestra silent for a long time, leaving the development to the violin - expressed in the old sonata form category. Only when the violin increasingly finds its own playing and rhythm does the orchestra rejoin, discreetly and colourfully accompanying the violin solo, which has found its own way to play freely. The violin imaginatively varies its secondary motif, plays its "glissandi" and "saltandi" with freedom. The violin seems to enjoy the moments of exuberance until, at the end, the orchestra and the whip strike again violently. Time for something different, second movement!

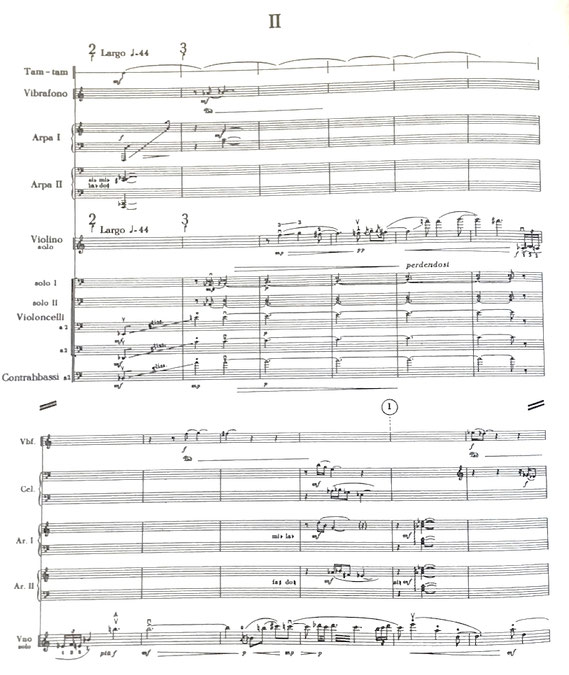

II. Largo

With a dark glissando of the cellos and basses to tam-tam, harp and vibraphone sounds, the orchestra creates a strangely unreal mood. It forms the background to a searching violin part that again circles around secondary intervals and spreads out over a wide area. It almost seems to lose itself in this unreal world of sound. Then this surreal soundscape is heightened by xylophone rhythms into the almost uncanny. The violin enters a second time, and the motif of the first movement, which circles around a single note (this interval filled within a minor third), reappears. It leads to striking melodic secondary downward movements, first in the solo violin, then quietly taken over by the orchestral violins. The violin increases and transforms this downward movement into a strangely enchanting sound world, which leads to a shimmering glissando melodiousness of the violin, which, however, becomes more and more sinister underneath. Against this, the violin insists fiercely with a single-note motif, and the orchestra also becomes loud. After a short exhaustion, the violin opens a new sound world with double stops, which leads to an almost mystically bright playing of the violin with vibraphone and celesta and finally leads into fast up and down movements of the violin, reminiscent of the first movement. A kind of cadenza follows, the quiet tremolo "sul tasto" of the violin leads into far-reaching leaps of tone, then the violin once again brings the slowly fading single-note motif in a gently dissonant variation to the sounds of the harp and bongo. A spherical, chorale-like woodwind song follows. Sudden horn blasts lead to screaming outbursts of the orchestral violins, the solo violin intervenes and calms the action. It unexpectedly finds space and silence, only to slip away into the farthest reaches of the world over soft tam-tam.

III. Allegro

After this original, almost surreal sound world of the second movement, Grażyna Bacewicz follows the convention of violin concertos and adds a third movement in recognisable 6-8 time, lively, as befits a violin concerto, but equally novel in sound and violinistic virtuosity. The violin plunges into the action with verve, again in upward and downward movements, but now brashly determining the onward rush. The orchestra follows the self-confident violin and rhythmically and colourfully accompanies the violin's constantly new up and down movements. Briefly, the orchestra takes over the action in a wild upswing and wants to set the pace with the help of bongos. But then the violin calmly but firmly enters with its single-note motif, sings its song freely in full violin tone and ends up again with its own almost manic up and down movements from the beginning of the movement. Even when the orchestra joins in again, the violin charges ahead unchecked and manically virtuosic, until the onrush leads into a tonally enchanting pizzicato section. After this brief calming, however, the violin continues in a lively and virtuosic manner. Once again a brief moment of rapture, once again the violin reveals its motif circling around a single note. But then everything turns into a wild final spurt. The violin can once again live out its manic virtuosity at a wild tempo, until everything ends with a violent crack of the whip. Unlike the threatening whip crack at the beginning of the concerto, the final whip crack seems to sound more liberated after the wild ride through all these sound worlds.