Julia Perry: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1963 - 1968)

Julia Perry

Born 25 March 1924 in Lexington, Kentucky, USA

died 24 April 1979 in Akron, Ohio, USA

Composition and première

Composed between 1963 - 1968;

first performed February 2022 by Roger Zahab

Recordings:

Roger Zahab (2022) on Youtube

Curtis J. Stewart (2023) on CD

Julia Perry enjoyed astonishing success both in the USA and in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s after receiving a good education as a musician. She conducted her works with the Vienna Philharmonic and the BBC Orchestra. She became one of the first African-American composers to have her orchestral works performed by the New York Philharmonic and other major American orchestras. Although she had a promising career in her early life, it was tragically cut short by a series of strokes that left her partially paralysed and eventually led to her death at the age of 55 in 1979. Her works disappeared from the public eye. As a result, Julia Perry is one of the unusually quickly forgotten composers because she was not only a woman and ill, but also belonged to the disadvantaged US population of colour in the 20th century.

Julia Perry was a violinist, conductor and composer who first studied with Luigi Dallapiccola at Tanglewood in 1951, where she completed her Stabat Mater for soprano and string orchestra and performed it with great success. Dallapiccola supported her, she came to Europe and later also studied with Nadia Boulanger. The Stabat mater dedicated to her mother, in particular, launched Perry's career and became the most frequently performed work of her life.

Julia Perry enjoyed astonishing success both in the USA and in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s after receiving a good education as a musician. She conducted her works with the Vienna Philharmonic and the BBC Orchestra. She became one of the first African-American composers to have her orchestral works performed by the New York Philharmonic and other major American orchestras. Although she had a promising career in her early life, it was tragically cut short by a series of strokes that left her partially paralysed and eventually led to her death at the age of 55 in 1979. Her works disappeared from the public eye. As a result, Julia Perry is one of the unusually quickly forgotten composers because she was not only a woman and ill, but also belonged to the disadvantaged US population of colour in the 20th century.

Julia Perry was a violinist, conductor and composer who first studied with Luigi Dallapiccola at Tanglewood in 1951, where she completed her Stabat Mater for soprano and string orchestra and performed it with great success. Dallapiccola supported her, she came to Europe and later also studied with Nadia Boulanger. The Stabat mater dedicated to her mother, in particular, launched Perry's career and became the most frequently performed work of her life.

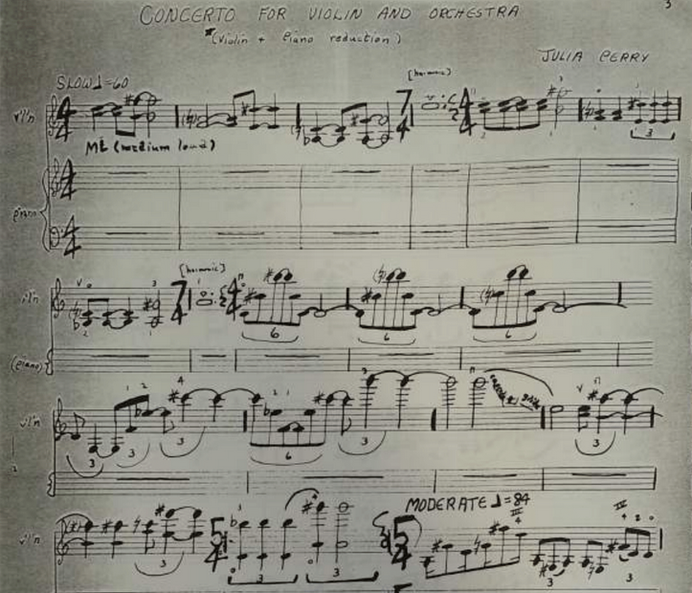

Composed between 1963-68, the violin concerto, which was never performed during her lifetime due to her illness, represented a compositionally independent contribution to the serial and atonal music of her time. Even the formal structure of the concerto defies the tradition of three movements and creates a varied sequence of changing tempo, motif and formal sections. In order to immerse oneself in Perry's musical language, it helps to visualise the context of the time, both politically and in terms of music history. In addition to Dallapiccola, his musical role models include composers such as Schönberg, Bartok, Berg and others, who sought new harmonies, forms and orchestration for solo and orchestra in their concertos. New political upheavals also characterised contemporary events in the USA: the presidency of John F. Kennedy, the fight for the abolition of racial segregation, Martin Luther King's civil rights movement, the protests against the Vietnam War, the student movement at universities and the emergence of the feminist movement. Julia Perry lived through this era of upheaval in the USA. Breaking out into new musical and tonal dimensions was also the programme for composing her own violin concerto. Perry completed her violin concerto in 1968, but it took more than four decades for the composer Roger Zahab to reconstruct the final score. The work was not premiered until 2022.

The following listening guide will help you to pay attention when listening to this unusual violin concerto. It is based less on the compositional technique of the work (I refer to the

dissertation by Clara Nicole Fuhrman, available here), but is orientated towards the timing of the immediate listening experience. This remains subjective, but follows the sound and form of this

23-minute violin concerto as closely and attentively as possible, from the opening cadenza to the vehemently ending final cadenza. It is fascinating to listen to how consonant and dissonant

sounds mingle, even reconcile, to create a lyrical style that is very special to Perry and unusual for the violin.

Formally, the concerto is composed without sections; individual sections differ according to the three fixed tempi, which alternate 13 times: Slow (slow crotchet = 60), Moderate (crotchet = 84),

Fast (crotchet = 120).

Listening companion:

I Slow

Three times two painful double stops, alternating between consonant and dissonant, and a high, lonely, quiet flageolet note in response, from which the violin develops a lyrically expressive first solo cadenza right at the beginning. Recitative-like, varying and continuing the initial sound motif, the violin determines the sound character of the coming concerto events from these initial double stops and develops the first melodic movements from them. The opening motif can be recognised again.

II Moderate

A rhythmic pattern soon emerges in the solo violin's playing, which enlivens the double-stop sounds. The cadenza expands in an ascending and harmonic manner and ends in the violin with a long

dissonant-consonant triple stop on D and C.

The violin then switches to fast fifths. The orchestra joins in with deep pizzicati in the background. A brass choir joins in, reminiscent of Afro-American brass bands. However, the gentle,

lyrical mood remains and also spreads out into wide sound spaces in the orchestra. Rhythmic rocking movements on the note D move the action forward. Violin sounds and new orchestral colours

intermingle.

III Fast

The flutes introduce an orchestral interlude. Lyrical sound mixtures light up and rhythmic brass figures emerging in the depths enliven the musical events with gentle energy. A xylophone with a timpani roll interrupts and briefly marks a kind of disturbance, while the gentle orchestral interlude continues unperturbed and magically for a long time until a triple percussion eruption concludes the orchestral interlude.

When the solo violin re-enters over cutting woodwind chords, a basic rhythmic pattern becomes perceptible in the violin figurations, consisting of fast, swaying quaters and three quater triplets. Violent xylophone interjections then lead to a trumpet quater motif that takes up this basic rhythmic pattern.

IV Moderate

Gentle string sounds overlay these fading wind rhythms.

A new, rather mechanical section becomes perceptible when the violin changes to regular pizzicato quarters in 5/4 time and the orchestra throws in its interjections in blocks. After two harp chords, the orchestra's woodwinds and brass lyrically continue to sing their rhythmic figures in a melodious orchestral interlude.

V Slow

Imperceptibly, the violin gently enters again and joins in with this song. The orchestral strings blossom lyrically in a strangely beautiful blend of sound with the woodwinds. The double-stop sounds of the beginning reappear briefly on the solo violin.

VI Moderate

The previous rhythmic rocking quarter motif is again intoned by the brass and then immediately accelerated...

VII Fast

... and maintained in the orchestra for a long time.

These almost penetrating figurations of the orchestra create space. You are immersed in the magical soundscape of a strangely unreal brass band.

VIII Moderate

The violin reappears above harp sounds with its long, sustained violin notes. The harp lingers for a long time on its low A, other instruments join in and develop new sequences of timbres that harmoniously underline the lyrical violin sounds. The harp's low A echoes for a long time, while the violin lets its long violin notes fade away and then mixes with the various orchestral instruments in a new departure, without dominating them.

IX Fast

When the violin picks itself up again and takes its place at the head of the orchestra playing long accompanying chords, the tempo quickens. Now the violin animates and dominates the action again, leading to a kind of recapitulation of the beginning of the concerto in advancing figurations.

X Slow

The violin recalls the opening motifs of its cadenza at the beginning of the concerto, now supported by the whole orchestra. A fine-voiced orchestral interlude is heard above the tremolo of the solo violin, which varies the motifs from the beginning on different orchestral instruments. After short pizzicati and xylophone strokes, the solo violin and orchestra fade away on the low G.

XI Fast

The brass band then recalls its basic rhythmic motifs. The music celebrates its very own world of sound. The solo violin escalates into fierce figurations. Rhythmic timpani beats and the brass push forward.

XII Moderate

The violin plunges into another solo cadenza at a virtuosically high tempo, and its recitative-like opening movements and double-stopping sounds visualise the previous sound events once again. Once again, the solo violin sweeps us into a flow of movements, melodies and sounds.

Xiii Fast

Until a timpani roll introduces a vehement orchestral final spurt that brings the concerto to a fierce and decisive conclusion. What remains is the strong impression of having experienced something never heard before in the last 20 minutes.