Antonio Vivaldi: Concertos RV 226; RV 243; RV 254; RV 278; RV 314A; RV 333

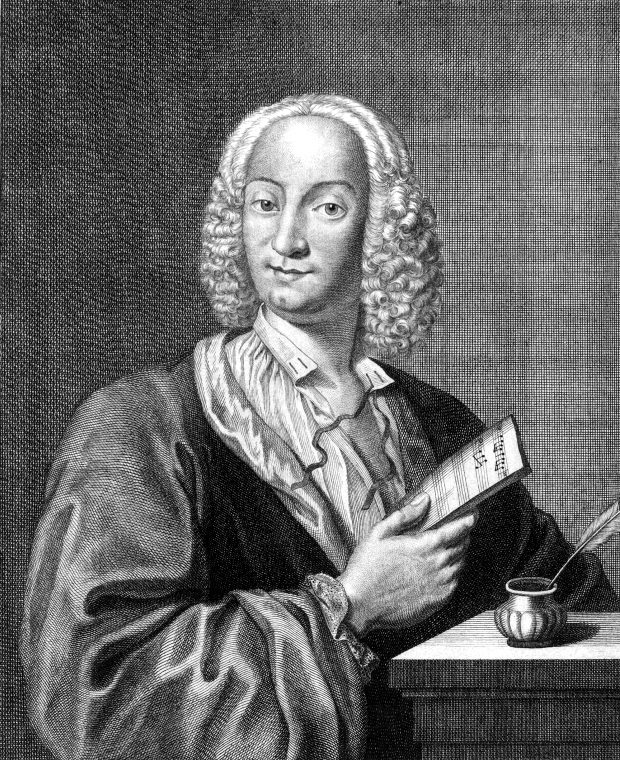

Antonio Vivaldi

born 4 March 1678 in Venice

died 28 July 1741 in Vienna

Time of origins:

Concerto in D major RV 226, after 2020-24

Concerto in D minor RV 243 ("senza cantin"): after 1729

Concerto in E flat major RV 254: after 1729

Concerto in E minor RV 278: around 1730, probably in Bohemia

Concerto G major RV 314a: around 1717/18

Concerto in G minor RV 333: around 1725

CD recommendations:

Giuliano Carmignola 2004

Anton Steck (2006)

Duilio M. Galfetti 2007

Giuliano Carmignola 2012

Amandine Beyer2014

Fabio Biondi 2017

Lina Tur Bonet 2018

Julien Chauvin 2021

Giuliano Carmignola 2023

Vivaldi is widely known today, especially because of his violin concertos "The Four Seasons". And Stravinsky is often quoted as saying that Vivaldi composed only one violin concerto, but 400 times. More precise knowledge of the violin concertos and the creativity of Vivaldi meanwhile makes this prejudice fade. Around 250 violin concertos by Vivaldi have survived, 100 of them in alternative versions (Olivier Fouré). Here, I can only discuss a few concertos that have caught my personal attention and that bear witness to the inventiveness of this Venetian composer. After all, his concerto form has written musical history.

Concerto D major RV 226, after 2020-24

Between 1716 and 1717, the Saxon Crown Prince Frederick Augustus and the Polish King Augustus III visited the city republic of Venice. Their court musicians were also present. The result was

that the new style of Italian music subsequently spread to Germany and Poland. Among these musicians was the violinist Johann Georg Pisendel, who befriended Antonio Vivaldi and was allowed to

copy his violin concertos and take them back to Dresden for his own use.

A manuscript of Concerto RV 226 therefore still exists today in Dresden (probably a copy for Pisendel), as well as a copy in Turin, where many of Vivaldi's manuscripts are kept and have

recently been re-examined. Thanks to the Internet, these two copies can be viewed and listened to. An interesting insight into the workshop of musicians of the time. Vivaldi's corrections in the

Turin manuscript also stand out. What sounds so easy seems to have been worked out thoroughly and precisely. Even if the usual three-movement, fascinating concerto only lasts just over 8

minutes.

Compare:

Manuscript in the Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria, Turin (I-Tn): Giordano 29 (f.182r-189v) with

corrections by Vivaldi

Manuscript in the Sächsische Landesbibliothek, Dresden (D-Dl): Mus.2389-O-104 Schrank II coll.copy, copy

probably for Pisendel

Listen here!

I. Allegro

A special feature is noticeable right at the beginning: The opening ritornello, normally reserved for the full orchestra, is immediately joined in by the solo violin. A descending unison theme

enters twice in the basses with rhythmically striking determination. The solo violin immediately counters this twice with a decisive downward figure before suggesting a conclusion to the

ritornello with a simple rhythmic melody in double stops. However, the basses insist against the premature violin solo and play their rhythmic unison theme again. "Concertising", i.e. arguing

while playing, they find a joint conclusion to the opening ritornello.

Only now should the solo violin begin to play in concert, which it does immediately. This and the following solo sections of the violin present completely different variations of alternating solo

figurations, which alternate with the unison theme that appears again and again as a ritornello.

Can images be projected into this score as a listening aid? If it is an aid to listening, why not? Vivaldi loved to evoke pictorial associations with sounds, and not only in the Four Seasons. Can

you also hear a wild ride, hunting horns or even cannon salvos and the trampling of horses? Whatever the case, translated into the modern age, one could say that it is the joy of speed, mobility

and freedom that resonates with us.

II. Largo

And Vivaldi follows this lively ride through time with one of his most beautiful slow movements. The opening pizzicati in the strings already give us a hint of something special. A magically beautiful melody in the solo violin with its ornamentation opens up the listening space into the expansive and transcendent. Just listen and go with it, no more images are needed here! At the end, the last pizzicato sounds of the strings give us some time to come down from our amazement.

III. Allegro

The beginning of the final movement brings us back to the hurried ride through time. A full D major string sound in syncopated forward motion characterises the ritornello, which concludes with two unison passages up and down. The violin solo parts (which now begin correctly!) fantasise their figures in a constantly driving rhythm, impressing and captivating us listeners. They are interrupted from time to time, but not stopped, by the unison passages of the ritornello finale, which then - in the logic of this concerto, so to speak - also form the end of the concerto.

Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto d-moll RV 243 («senza cantin”)

When Vivaldi's surviving violin concertos were composed cannot be clearly determined in Vivaldi research; many sources are missing. The Concerto RV 243 seems to have been composed after 1729,

but musicologists do not know exactly when. Its peculiarity: the violin never plays on the top string, the e-side or the cantin (the singer's string).

The violin therefore deliberately restricts its singing and still comes across beautifully.

I. Allegro

The concerto begins in the dark key of D minor. Repetitive phrases follow one another, the narration is rather dark. Then the violin enters, also with repetitive figures, she brings in her voice quietly, not dazzlingly dominating, but rather discreetly. As if she were withdrawing, she then leaves the music to the ripieno of the orchestra again. The violin sticks to its shadowy sound figures, alternating with the orchestra's playing and hastening towards a rather resigned conclusion of the orchestra.

II. Andante molto

Vivaldi's middle movements often take us very briefly into a new, different world, as if they wanted to whisk us away from everyday life. In this concerto, too, the violin begins to sing a melody, always on the somewhat melancholy-sounding high register of the A string. The violin plays its rapturous song in a contemplative and somewhat sad manner.

III. Allegro

The orchestra begins with a rhythmically determined and dance-like stomping, the violin joins in this dark whirling dance, with a new scordatura, the G string tuned to A, but the mood doesn't quite want to lighten up. Not until the end! The music drives forward energetically. Always discreetly virtuosic, the violin is at the centre. But figurations and a kind of short cadenza at the end prove that it could do more: It could do more.

Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto Es-Dur RV 254

This concerto RV 254 probably dates from the same period as Vivaldi's Violin Concerto RV 243.

Listen here!

I. Allegro

The concerto begins with an insistent, march-like rhythmic motif in the orchestra, punctuated by violin interjections. From E-flat major, the harmony changes briefly to G minor, giving the theme a characteristically serious note. Finally, the violin takes the lead, confidently and with a melody that it carries on with relish until the rhythmic motif of the orchestral tutti interferes again, first in C minor and then in G minor. But then the violin gets going, virtuoso bariola passages show who dominates and what the violinist can do, then the ripieno tutti follows again in ritornello form, and once again the violin shows what double stops can do in the next solo section, conveying serious, mature joie de vivre. A short final tutti, as if the orchestra were withdrawing.

II. Largo

Tension builds up in the orchestra, the basses push forward, with slow upward passages the violin then takes over the melody, peaceful and melodious, as if it wants to tell of love and beautiful feelings? Just follow it, it takes you along, the orchestra accompanies with discreet chord playing. At the end, the basses once again interject themselves weightily... as if they wanted to put a stop to it.

III. Allegro

Here, too, the basses drive forward, in fast, regular piano. Then the violin takes the reins again. After all, it's all about her. In wild lust, it rushes forward, only briefly pausing in between to return to the Largo. But immediately she pushes on, outshines and convinces the scanty orchestral tuttis. After all, it's all about the violin, it gets to show what it can do. And Allegro comes from Allegria, E-flat major- joy. And mature, serious joy makes you strong.

Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto e-moll RV 278

The manuscript of this concerto was found in a corpus of Vivaldi's compositions collected in Prague and Bohemia between 1730 and 1731. It seems that the concerto is gaining popularity among

baroque violinists after its first recording by Giuliano Carmignola in 2004.

Here is a live concert recording on Youtube with Midori Seiler and

the Bremen Baroque Orchestra from 2016!

I. Allegro molto- Andantino

Like a wild storm, a string tutti races towards the listeners to stop immediately: The sighing motifs of a Largo interlude immediately trigger other emotions. Once again the storm, only then "andantino" an almost dance-like fading of this emotional contrast, leading from the dominant to the tonic. The E minor storm, however, is still present, comes again and closes the first ritornello tutti. The soloist announces himself with a painful cantilena, then covers his emotions behind virtuoso violin brilliance: great leaps, sixteenth-note figures, leaping arches and rhythmic restlessness. After a brilliantly wild run of the violin, the stormy tutti falls in again. But the soloist continues to escalate into almost bizarre gimmicks, without being able to conceal a latent despair. Again the stormy ritornello tutti, but after a brief halt it threatens to flag. With a wild run, the violin comes to the fore again and dominates the scene with its daring, virtuosic, but also vocally varied rhetoric, until the expected tutti that closes without surprise.

II. Largo

An astonishing beginning: Vivaldi prescribes long, mysterious string chords that take unusual harmonic courses. A bass rhythm underlies everything, almost a kind of dead conduct, depending on the interpretation. Sighing motifs follow, the tutti withdraws and leaves the lamentation to the violin. What follows is what always fascinates listeners of Vivaldi's music: a solo melody over an infinitesimally quiet accompaniment, more intimate than opera singing, only the violin can lament in such a way and at the same time comfort us to weep beautifully. Simply sing along inwardly, and abandon yourself to the violin. The orchestra concludes the scene, fading away in peace.

III. Allegro

Stormy E minor mood again as in the first movement, but now rhythmically driven forward by the violas and basses.

A quiet middle section in the upper voices briefly interrupts the propulsive dynamics. The violin's first solo section joins in this fierce dynamic with energetic sixteenth-note figures, now with

its varied and, for the time, innovative violin technique: highest pitch, big leaps, fine sixteenth-note passages, runs, trill ornaments and double stops.

The tutti drives the breathless dynamics further. The middle solo section brings some peace in between, even if the rhythmic drive carries through. The violin's final solo also shows its melodic

possibilities, contrasting with wild leaping arcs and the breathlessness of the movement. The character of this movement might well be called stress today. The tutti concludes as usual with the

opening ritornello.

Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto G-Dur RV 314A

Vivaldi composed this agile, spirited and yet also lyrical violin concerto in G major expressly for the violinist Johann Georg Pisendel ("per Monsieur Pisendel"), who was on friendly terms with Vivaldi during an extended stay in Venice. Music unites friendship, one could write as a motto about this concert. In return, Pisendel copied various Vivaldi concertos to perform them on his return to Dresden with the famous court orchestra there. RV 314 is one of these violin concertos and probably dates from 1716/17, the middle period of Vivaldi's creative work.

I. Allegro

A typical Vivaldian ritornello theme immediately sweeps us along. It consists of a gripping, swinging short motif, whose quiet repetition and decisive continuation lead to a surprising chromatic passage, which then leads to the first violin solo. Already here, Pisendel was able to demonstrate his speed in sixteenth-note runs, his wide bow jumps and double-stopping technique. Then the ritornello theme intervenes again, until the violin gets going again in the second solo with the fastest triplets and only plays a calm chromatic transitional phrase during the transition to the third ritornello (in E major this time). The violin begins the third solo with a recumbent string accompaniment, now with a lyrical, chant-like Adagio phrase. Then the ritornello theme follows again and leads joyfully to the conclusion.

II. Adagio (Cantabile)

The middle movement of this G major concerto has survived in two versions. One is an Adagio cantabile, a kind of sonata middle movement with repetitions and bare basso continuo accompaniment. The

other is an enchanting Adagio (RV 314a) with pizzicato accompaniment by the strings, over which one of Vivaldi's wonderful lyrical aria melodies blossoms and almost dies away in beauty with its

ornaments.

Listen to RV 314 here!

Listen to RV 314a here!

III. Allegro

Again, an almost simple, descending ritornello motif, answered by quiet vibrating eighth-note scales that recede into pianissimo. The violin solo that follows again goes its own virtuoso way. In the next tutti, the descending ritornello motif is reversed and runs upwards (only in the violas still downwards!) without losing its character. The violin's second harmonically interesting solo then leads to a tutti consisting entirely of the eighth-note scales, which now seem electrifying and are electrified even more by the solo violin's sixteenth notes. After a brief pause, the violin takes over again and lets its triplet runs wander through the most varied harmonies and chromatic passages until the upward ritornello theme interrupts the violin playing (the violas also play upward from now on, as the last to do, as a glance at a detail of the score proves). With momentum, it then quickly moves to the effective conclusion.

Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto in G minor RV 333

Rather sombre and mysterious, and yet upbeat and with drive, that is how one could describe the character of this violin concerto. Vivaldi did not publish this concerto in any of his

collections or have it published elsewhere. Did he reserve it for his own solo performances, or was it suitable as an intermission encore in performances of tragic operas? The very question of a

seat in life remains speculation. What has survived is the manuscript of the concerto, whose interpretation produces music of strangely profound content, but also of thrilling rhythm. Vivaldi

used the second movement again in a sacred context in RV 556, newly orchestrated for clarinet and violin. Something profoundly ineffable pervades the course of this G minor concerto. It was

probably composed around 1725.

Listen to RV 333 here!

I. Allegro

The opening immediately attracts attention with its rhythmically halting and double forte-piano texture. In addition, G minor alternates with B flat major in the opening theme. Only then does a

chromatically gloomy mood dominated by syncopation spread out, which is shortly underpinned from the depths by a bass figure similar to Bordun. Moving figures lament over it, until a fierce basso

continuo solo marches forward and drags the ripieno orchestra along with it. The tutti ritornello then flows smoothly into the violin's first solo.

On rhythmically regular eighth notes, the violin exudes its consistently vocal and at the same time virtuoso figures until residual motifs from the initial ritornello interrupt its solo playing.

The ritornello motifs of the beginning follow each other freely and almost like a development, and again almost unnoticed, concealing the ritornello structure, the solo violin enters with its

eighth-note figures and triplet runs and leads us through the most diverse keys. Solitary long-drawn-out high violin notes bring some calm, lonely second violins briefly enter below with a

descending and ascending accompaniment of the solo voice, until the ritornello theme, marked by syncopation, energetically interferes again.

It is immediately replaced by melodious arches and rhythmically imaginative figurations of the solo violin. Once again, a sombre ritornello-like interlude from the orchestra. Dancingly, the solo

violin then charges towards a kind of virtuoso solo cadenza. Insisting on the sombre ritornello mood, the orchestra once again sets its accents and leads the formally rather free movement to a

decisive end.

II. Andante Cantabile

The second violins play a lonely and monochrome striding, immediately catchy bass theme, which then has to serve as an accompaniment for a cantabile violin solo. One continues to listen both to the accompaniment, but also allows oneself to be enchanted by the violin solo and goes along on a short solitary journey for two until a peaceful conclusion. A Vivaldi middle movement not to be forgotten!

III. Allegro

6 times a sharp G and 6 times a D: thus begins a wild fughetto of the strings in triple time (or is it a duple time, all still veiled and unclear at the beginning!).

The fughetto finally pours into lively eighth notes, always driven by the rhythmically accentuated notes and caught in a triple time. Syncopations accentuate the dynamics. This ritornello ends in

unison (with an echo effect) and leaves the violin in the lead.

Accompanied in unison by the violins, the solo violin moves along its tied eighth notes. The riternollo reappears ingeniously, the basses continue the tied eighth notes, while the upper voices

introduce the ritornello theme with the typical 6 pointed notes. Again, a unison of the ripieno instruments leads to the violin solo.

Dancing and constantly varying figures of the solo violin fit into the triple time and let the movement blossom, again and again briefly interrupted by ripieno interjections.

Melodically, the movement then moves on to another ripieno with the typical 6 pointed notes. A funny back and forth of triplets between basses and solo violin give this movement further momentum

and culminate in the integral repetition of the ritornello in the home key. This time, however, the solo violin decisively accompanies the ritornello with virtuoso appoggiaturas and in turn

emphasises the climax of this movement.

At the end, the solo violin once again sounds complicated and surprising passages in triple time and accelerates its playing to virtuoso triplet runs. The concerto ends in the unison of the

ripieno (with a renewed echo effect).